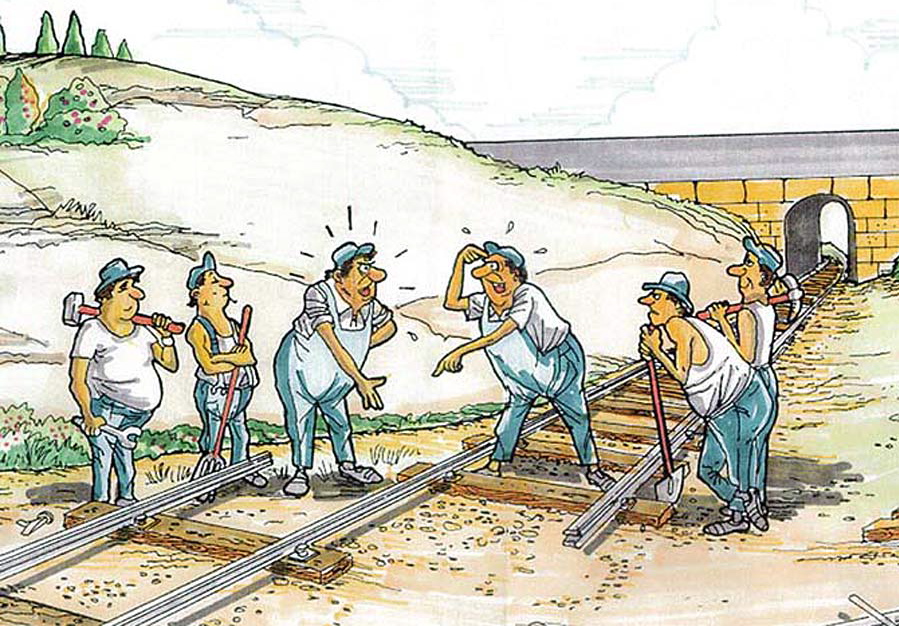

A group of my students were working on a team project, and were experiencing some problems getting their act together. Nothing too serious, just the sort of symptomatic problems that seem to get in the way of top-notch performance from team efforts.

A group of my students were working on a team project, and were experiencing some problems getting their act together. Nothing too serious, just the sort of symptomatic problems that seem to get in the way of top-notch performance from team efforts.

Why do we seem to have problems working together on teams? Everybody knows about Teamwork. In simplest terms, teamwork is working together with others to achieve a common goal. Look up teamwork in the dictionary and an additional element emerges. According to Merriam-Webster, teamwork is:

“work done by several associates with each doing a part but all subordinating personal prominence to the efficiency of the whole”

so there seems to be a requirement to sublimate egos in the pursuit of the team goals.

And, of course, all of the members of the team have to be working in a coordinated way to achieve an agreed upon goal, or the results can be disappointing, or worse….

Surprisingly, the word, “teamwork” hasn’t been around for all that long. The ancient Greeks and Romans had no word for teamwork. It first showed up in the English language in the 1820’s, from a simple combination of the words team and work.

Teamwork isn’t a concept limited to homo sapiens. Team-like behavior in the animal world is so common that Ken Thompson has fashioned the term bioteaming to describe the application of behaviors found in nature to the work of teams in human organizations.

There are countless examples of so-called symbiotic relationships in the animal world. The remora is a fish that attaches itself to larger fish like sharks, sometimes to whales, much like getting on a bus for easy transport through the oceans. The Egyptian plover is a bird that feeds on bugs and debris caught up in crocodile’s teeth – saves the croc a trip to the dentist while making dinner a thrill ride for the plover.

Social insects like bees and ants demonstrate the importance of different actors playing out clearly defined roles. Wolves learn to hunt in packs, chasing down and overwhelming larger prey through coordinated attacks. Canada geese flying in formation trade-off the “lead bird” role; when the bird flying at the point of the V-formation begins to tire, it moves to the back and another bird moves up to take on the more tiring lead role. Even our canine companions sometimes work together to do what they couldn’t accomplish on their own.

Social insects like bees and ants demonstrate the importance of different actors playing out clearly defined roles. Wolves learn to hunt in packs, chasing down and overwhelming larger prey through coordinated attacks. Canada geese flying in formation trade-off the “lead bird” role; when the bird flying at the point of the V-formation begins to tire, it moves to the back and another bird moves up to take on the more tiring lead role. Even our canine companions sometimes work together to do what they couldn’t accomplish on their own.

Nonetheless, with all of the advantages that we have over bees, ants, birds, fish, dogs, cats, and other animals, we still have trouble forming and performing as teams. I think what may be needed is a way of looking at Teamwork as a concept that represents a set of values that encourage listening and responding in ways that provide support and cooperation, giving the benefit of the doubt, and making it as easy as possible for all team members to contribute as richly as possible to the team effort.

Over the years I’ve collected a set of guidelines or rules that can go a long way toward delivering strong team performance. The rules are personal and deal only with our own behavior, NOT what the other members of the team are doing.. That makes sense to me, since the only person’s behavior I can control is ME.

Now, I certainly don’t want to imply that I am in any way, shape or form a Paragon of Pure and Perfect Team Play. Too often I tend to act as if I am the only one who really knows what to do and how to do it. Arrogant and abrasive are adjectives that come to mind. Those who have worked with me can verify that. Regardless, I’ve seen that when I do behave like a good teammate, I can dramatically improve the chances that the team will perform well. I’m not ready to get out the hammer and chisel and engrave these rules on tablets of stone, but here are my Ten Commandments of Teamwork:

- Don’t make quick judgments about the capabilities or potential to add value of other members of the team, especially if they are negative judgments.

- Don’t be a smug, pompous, know-it-all ass. Help build a team, not your ego.

- Be open and trusting toward other team members if you want them to trust you.

- Be able to work with and learn with other people who will be thinking about things in different ways and at different speeds, than you are. Lots of people won’t be flying at the same altitude as you are. Accommodate them.

- Don’t argue. Stay off the soapbox, but don’t avoid confronting issues that arise. Find a non-argumentative way to get to the heart of issues without getting personal.

- Don’t give up and start flailing if things don’t work out well on the first attempt. Put your best efforts into every attempt. Don’t dwell on past successes or failures, beyond what can be learned from them. Live in the moment and make NOW the best possible now; then move on.

- Work hard to build a broad network of contacts; this will enhance the flow of information, which is the key to good decision-making.

- Acknowledge and share your personal agenda, but be ready to dispose of it if it’s not going to help move the team toward it’s goals.

- You can’t always pick you teammates, but never pick on them. Help them if you can, but don’t overdo it. Admit that you’re not always right.

- Keep a big picture perspective, but remember that, in the end, the down-to-earth details are what usually make the difference between success and failure.

What do you think?

A student in one of my Leader Development Program sessions was grappling with his role as a leader in his organization. He felt that he had never sought out a leadership role, and wasn’t sure that it was something that he really wanted to do.

A student in one of my Leader Development Program sessions was grappling with his role as a leader in his organization. He felt that he had never sought out a leadership role, and wasn’t sure that it was something that he really wanted to do.