Have you ever wondered why peacocks developed such long, beautiful tails? It’s simple evolutionary biology. Peahens show a reference for large-tailed peacocks. In the earliest days, this made a lot of sense. A showy tail was a marker of a good, healthy male who knew how to feed himself — a good breeding partner, and thus a smart choice for a peahen concerned about preserving her hereditary line. Well-feathered males thus had more opportunities to breed and pass on the long-tailed trait. Successive generations of peacocks had longer and longer tails.

Have you ever wondered why peacocks developed such long, beautiful tails? It’s simple evolutionary biology. Peahens show a reference for large-tailed peacocks. In the earliest days, this made a lot of sense. A showy tail was a marker of a good, healthy male who knew how to feed himself — a good breeding partner, and thus a smart choice for a peahen concerned about preserving her hereditary line. Well-feathered males thus had more opportunities to breed and pass on the long-tailed trait. Successive generations of peacocks had longer and longer tails.

This turned out to be a good thing for a while, but after many generations the extremely long tails created problems for the strong peacocks. The peacock’s long tails are physically “expensive.” They require a large amount of nutrients to grow and maintain in good health. But the bigger problem is the sheer weight of the peacock’s tail. The heavy tail slows the peacock, making them highly susceptible to predators. Over time, the tails got longer and longer, while the population of peacocks got smaller and smaller. For peacocks, it was a form of biological suicide. The only thing that has saved peacocks from extinction is human intervention — we protect them because we feel they are too beautiful to allow them to disappear from the face of the earth.

This turned out to be a good thing for a while, but after many generations the extremely long tails created problems for the strong peacocks. The peacock’s long tails are physically “expensive.” They require a large amount of nutrients to grow and maintain in good health. But the bigger problem is the sheer weight of the peacock’s tail. The heavy tail slows the peacock, making them highly susceptible to predators. Over time, the tails got longer and longer, while the population of peacocks got smaller and smaller. For peacocks, it was a form of biological suicide. The only thing that has saved peacocks from extinction is human intervention — we protect them because we feel they are too beautiful to allow them to disappear from the face of the earth.

What does a peacock’s tail have to do with any of us? Under pressure, we all revert to our strengths, whether or not the behavior pattern is appropriate. We come to believe that our perceived strengths are always going to be able to win the day for us. As a result, we “do what comes naturally,” even if it wasn’t always “natural,” but is simply a habit that we have fallen into because it worked most of the time. It’s easy enough to figure out why this is so. We crave approval, so we overreact to praise for strengths. We become a sort of one-trick pony, even when that trick is inappropriate.

What does a peacock’s tail have to do with any of us? Under pressure, we all revert to our strengths, whether or not the behavior pattern is appropriate. We come to believe that our perceived strengths are always going to be able to win the day for us. As a result, we “do what comes naturally,” even if it wasn’t always “natural,” but is simply a habit that we have fallen into because it worked most of the time. It’s easy enough to figure out why this is so. We crave approval, so we overreact to praise for strengths. We become a sort of one-trick pony, even when that trick is inappropriate.

Of course, sometimes we can fall into the same type of habit without being encouraged by praise. Instead, we simply listen too well to conventional wisdom. We follow the rule that if taking a spoonful of medicine is a good thing, then drinking down the whole bottle should be a great thing. It’s easy enough to pooh-pooh this idea as ridiculous, but consider how often it plays out in our own lives. For example, many of us exercise to improve our strength and overall health, but there’s always a break-even point. When we over-exercise, we no longer become stronger. Instead, we strain our muscles, hurting ourselves in the process, and actually decreasing our performance.

Of course, sometimes we can fall into the same type of habit without being encouraged by praise. Instead, we simply listen too well to conventional wisdom. We follow the rule that if taking a spoonful of medicine is a good thing, then drinking down the whole bottle should be a great thing. It’s easy enough to pooh-pooh this idea as ridiculous, but consider how often it plays out in our own lives. For example, many of us exercise to improve our strength and overall health, but there’s always a break-even point. When we over-exercise, we no longer become stronger. Instead, we strain our muscles, hurting ourselves in the process, and actually decreasing our performance.

The same kind of thing can occur with over-exercising our strengths. Our overall performance could decline, because we continue to repeat behaviors that worked for us in the past, but no longer serve to get the job done. Our former strengths, when overplayed, can actually become a weakness. When that that happens, the same strengths that supported our successes can turn into professional liabilities. It’s important to make sure that doesn’t happen to you, or to the people that work for you.

Consider these examples:

- Joan was considered one of the best people in her department at consensus building. When she was placed in charge of a large, deadline-sensitive project, Joan spent so much time trying to make sure that everyone on the project team was in agreement on every aspect of the project, that the project fell hopelessly behind schedule and she had to be replaced.

- Bill was able to inspire his team because he always spoke and acted with supreme confidence. He ran into problems when his self-confidence led him to arrogantly dismiss anyone who disagreed with him.

- Ricky’s persistence helped him push through to completion on projects that stymied others. He finally lost his job when his persistence turned into blind obstinacy, and he kept pushing forward on a project in spite of compelling evidence that there was no chance for success.

- Marie’s attention to detail saved the day on many projects. But when that diligence started to border on perfectionism, her team rebelled.

Any of the individuals in these examples could be a valuable contributor to your team, but it’s easy to see how their strengths, overplayed or used at the wrong time or in the wrong place, could turn into a debilitating weakness and impair overall team performance.

If you are like me, you may see a little bit of yourself in Joan, Bill, Ricky or Marie. So far, so good. Recognizing that you want to improve is a good first step. Figuring out what to do about it is the trickier part. On one hand, you need to be able to build, grow and flex your strengths to achieve personal satisfaction and professional success. On the other hand, you also need to be able to learn when over-exercising your strengths gets in the way of personal and professional growth.

How can you learn to change your approach while still maintaining confidence in your own strengths? These ideas might help you find the right balance:

Look first at how your strengths have contributed to your success. Describe your strengths; take the time to write them down in your notebook. Think about when you normally exert them? How have they contributed to your success? In which situations do the strengths have the most positive impact? How do others react to these strengths? What are the outcomes after flexing the strengths? The goal here is to determine when the strengths were demonstrated appropriately and effectively. If you have a coach or a mentor, make sure to get their perspective on the situation.

Consider the flip side — when your strengths have detracted from your success. Describe a time when exerting one of your strengths did not produce the intended results. What was the circumstance? Who was involved? What was his or her response? What was the ultimate outcome? Dialogue with your coach or mentor can play a particularly helpful role at this stage, since we are often completely unaware of how people react to our behaviors, especially when they are our “go-to-at-crunch-time” behaviors.

Identify the cues that can help you see when a strength becomes a liability or when the break-even point is reached. Compare the successful and unsuccessful scenarios. How did the circumstances or environments differ? How did the individuals involved in each circumstance respond differently? What other cues were present to reflect whether the strength was exercised effectively or not?

Create a plan to make yourself more aware of the break-even point in future situations. How will you modify your approach when cues arise indicating that a strength is becoming a liability? What feedback or other information will you need to ensure you are flexing strengths to support successful outcomes? Who will provide this feedback and when?

Because you have used your strengths and subsequently reaped rewards in the past, you might be reluctant to examine the possibility that your strengths have the potential to become problems. It’s easier to simply defend your current approach, blame others for being jealous of or threatened by your demonstrated strengths, or excuse your behavior by telling yourself that others are misinterpreting your intentions.

Don’t let it happen to you. Pay attention to how you use your strengths. Remember the peacock’s tail.

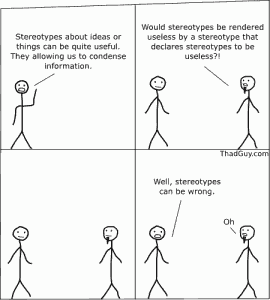

“For the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance. We are not equipped to deal with so much subtlety, so much variety, so many permutations and combinations. And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it.”

“For the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance. We are not equipped to deal with so much subtlety, so much variety, so many permutations and combinations. And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it.”