I got a gift the other day. One of my former coaches, Martha Tilyard (I wrote about Martha last year in my post “A Belated Thanks You“), sent me a link to a video of a 3-minute talk at the February 2010 TED by Derek Sivers, titled “How to Start a Movement.” I want to share that gift with you.

I got a gift the other day. One of my former coaches, Martha Tilyard (I wrote about Martha last year in my post “A Belated Thanks You“), sent me a link to a video of a 3-minute talk at the February 2010 TED by Derek Sivers, titled “How to Start a Movement.” I want to share that gift with you.

Mr. Sivers makes a few crucial points in his brief talk about leadership, focused on the role of the leader in starting a movement:

- A Leader needs the guts to stand up and be ridiculed.

- What the Leader does, and what she wants others to do, has to be easy to follow.

- The First Follower has a crucial role–showing everyone else how to follow.

- The Leader has to embrace the First Follower as an equal, so that the movement is not about The Leader (singular) it is about US (plural).

What it all comes down to is that the role of First Follower is a seriously underestimated form of leadership. It takes guts to get out there and be the first to follow a leader. In fact, it is the First Follower that transforms the “lone nut” into a Leader, because you can’t be a leader without at least one follower. Moreover, the act of following has to be a public act. If no one else can see it, what’s the point?

The great thing is that once the First Follower sets things in motion, it is that much easier for the second follower to join in, and, of course, three is a crowd. The momentum can build rapidly from that point. As more people join in, it’s less risky, the danger of ridicule drops way down. At that point, all of the fence-sitters join in rapidly, hoping to become part of the in-crowd, the first movers.

All of this got me to thinking, usually a dangerous situation. I wondered about a few First Followers:

In 1906 in South Africa, a lone nut named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi urged his fellow Indians living in South Africa to defy a new law requiring them to register with the government, and to peacefully suffer the punishments for doing so. Someone, unknown to us today, stood up and joined Gandhi, adopting the still evolving methodology of non-violent protest for the first time. The community adopted his plan, and during the ensuing seven-year struggle, thousands of Indians were jailed, flogged, or shot for striking, refusing to register, for burning their registration cards or engaging in other forms of non-violent resistance. At the time, who could have anticipated that the slightly built, bespectacled barrister who would become known as Mahatma Gandhi, would someday lead India to independence and inspire movements for non-violence, civil rights and freedom across the world?

In 1906 in South Africa, a lone nut named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi urged his fellow Indians living in South Africa to defy a new law requiring them to register with the government, and to peacefully suffer the punishments for doing so. Someone, unknown to us today, stood up and joined Gandhi, adopting the still evolving methodology of non-violent protest for the first time. The community adopted his plan, and during the ensuing seven-year struggle, thousands of Indians were jailed, flogged, or shot for striking, refusing to register, for burning their registration cards or engaging in other forms of non-violent resistance. At the time, who could have anticipated that the slightly built, bespectacled barrister who would become known as Mahatma Gandhi, would someday lead India to independence and inspire movements for non-violence, civil rights and freedom across the world?

Fifty years later, in June, 1956 in Indianapolis, Indiana (sorry about all of the alliterative ins) a 25-year old former member of the Communist Party USA, decided to organize a massive religious rally, riding the coattails of Rev. William M. Branham, a healing evangelist and religious author as highly revered by some at that time as Oral Roberts and Billy Graham. Someone thought the young man was worth following, and from that gathering, the Reverend Jim Jones started the congregation eventually known as the People’s Temple Christian Church Full Gospel. Twenty-two years later, on November 18, 1978, having moved the congregation first to Northern California near Ukiah, then eventually to Jonestown, Guyana , the Reverend Jim Jones presided over the mass suicide of 909 Temple members. Someone decided to follow the wrong lone nut.

Fifty years later, in June, 1956 in Indianapolis, Indiana (sorry about all of the alliterative ins) a 25-year old former member of the Communist Party USA, decided to organize a massive religious rally, riding the coattails of Rev. William M. Branham, a healing evangelist and religious author as highly revered by some at that time as Oral Roberts and Billy Graham. Someone thought the young man was worth following, and from that gathering, the Reverend Jim Jones started the congregation eventually known as the People’s Temple Christian Church Full Gospel. Twenty-two years later, on November 18, 1978, having moved the congregation first to Northern California near Ukiah, then eventually to Jonestown, Guyana , the Reverend Jim Jones presided over the mass suicide of 909 Temple members. Someone decided to follow the wrong lone nut.

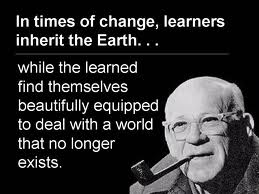

Maybe, as Mr. Sivers suggests, leadership is over-glorified. Sure, the Leader will be the one getting the bulk of the credit, but being a First Follower requires a lot of courage, maybe as much as the courage of the lone nut with a potentially world-shaking idea. The lesson for everyone who wants to be a leader is clear: nurture and support your first followers as equals.

And for those of us who choose to lead in a different way, maybe our best role is to find that lone nut with an idea that appeals to us intellectually and emotionally, and find the courage to turn that lone nut into a Leader, by becoming the First Follower. But remember, not every lone nut is created equal. Choose a Gandhi, not a Jim Jones.