I saw Steven Spielberg’s new movie, “Lincoln” and thought it was terrific. Daniel Day-Lewis gives a career-defining performance as Abraham Lincoln, and the supporting cast is outstanding. For slightly over two hours I felt as if I had been transported 148 years back in time, and was living through all the political turmoil at the end of The Civil War. But this isn’t a movie review. It’s a story about a hat. In particular, it’s a story about the formal hat that almost all of the men in Washington DC in early 1865 were wearing–the tall, stovepipe-shaped hat that we know as the Top Hat.

I saw Steven Spielberg’s new movie, “Lincoln” and thought it was terrific. Daniel Day-Lewis gives a career-defining performance as Abraham Lincoln, and the supporting cast is outstanding. For slightly over two hours I felt as if I had been transported 148 years back in time, and was living through all the political turmoil at the end of The Civil War. But this isn’t a movie review. It’s a story about a hat. In particular, it’s a story about the formal hat that almost all of the men in Washington DC in early 1865 were wearing–the tall, stovepipe-shaped hat that we know as the Top Hat.

The history of the top hat doesn’t have a clear-cut beginning. One story has the top hat invented in Florence around 1760. Another has a Chinese hatter making the first top hat for a Frenchman in 1775. What is known for certain is that an English haberdasher named John Hetherington caused a riot the first time he wore a top hat in London in 1797. According to a contemporary newspaper account, passersby panicked at the sight. Several women fainted, children screamed, dogs yelped, and an errand boy’s arm was broken when he was trampled by the mob. Hetherington was hauled into court for wearing “a tall structure having a shining luster calculated to frighten timid people.”

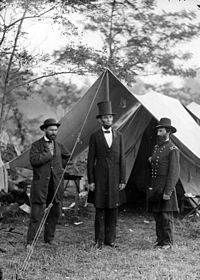

It was much ado about nothing, really; Hetherington’s top hat was simply a silk-covered variation of the contemporary riding hat, which had a wider brim, a lower crown, and was made of beaver. There was initial resistance to Hetherington’s silk top hat from those who wanted to continue wearing beaver hats. But around 1850 Prince Albert started wearing  top hats made of “hatter’s plush” (a fine silk shag), and that effectively settled the beaver versus silk fashion question. Of course, the fact that beaver trappers desire for beaver pelts to sell to hatters in America and Europe had all but wiped out the beaver population in America may also have had a lot to do with the switch from beaver to silk. Whatever the case, by Lincoln’s time the silk top hat was the de rigeur headwear for both informal and formal occasions. [The photo at left shows President Lincoln meeting his generals at Antietam in 1862.]

top hats made of “hatter’s plush” (a fine silk shag), and that effectively settled the beaver versus silk fashion question. Of course, the fact that beaver trappers desire for beaver pelts to sell to hatters in America and Europe had all but wiped out the beaver population in America may also have had a lot to do with the switch from beaver to silk. Whatever the case, by Lincoln’s time the silk top hat was the de rigeur headwear for both informal and formal occasions. [The photo at left shows President Lincoln meeting his generals at Antietam in 1862.]

Throughout the nineteenth century, men wore top hats for business, pleasure and formal occasions — pearl gray for daytime, black for day or night. The height and contour of the top hat fluctuated with the times, reaching a pinnacle [pun intended] with the French dandies known as “the Incroyables,” who wore top hats of such outlandish dimensions  that there was no room for them in overcrowded Parisian cloakrooms, until Antoine Gibus invented the collapsible opera hat in 1823. Nearly a century later, financier J. P. Morgan approached the same problem from another angle; ordering a limousine built with an especially high roof, so he could ride around without taking his hat off.

that there was no room for them in overcrowded Parisian cloakrooms, until Antoine Gibus invented the collapsible opera hat in 1823. Nearly a century later, financier J. P. Morgan approached the same problem from another angle; ordering a limousine built with an especially high roof, so he could ride around without taking his hat off.

My personal favorite top hat milestone was achieved in 1814 by a French magician named Louis Comte, when he became the first conjurer on record to pull a white rabbit out of a top hat. But by the early decades of the 20th century, the top hat was no longer

My personal favorite top hat milestone was achieved in 1814 by a French magician named Louis Comte, when he became the first conjurer on record to pull a white rabbit out of a top hat. But by the early decades of the 20th century, the top hat was no longer  everyman’s hat, but had become a symbol of the aristocratic and powerful, most famously evidenced by Rich Uncle Pennybags from the Monopoly game, and America’s Uncle Sam, a symbol of US power who is always shown with a top hat.

everyman’s hat, but had become a symbol of the aristocratic and powerful, most famously evidenced by Rich Uncle Pennybags from the Monopoly game, and America’s Uncle Sam, a symbol of US power who is always shown with a top hat.

Every US President since Lincoln wore a top hat to his inauguration, until Dwight D. Eisenhower broke with the tradition, which was briefly reinstated by John F. Kennedy at  his inauguration in 1960, and then abandoned by Lyndon Johnson and all the presidents who followed. Alas, in spite of its storied history, the top hat has largely gone out of fashion. There are, of course a few exceptions, like the iconic top hat that Slash, the guitar player from Guns & Roses adopted as part of his persona. But what was once commonplace has now become a rarity. It is, of course, still possible to purchase a silk plush top hat, though you’ll likely be buying a reconditioned model, re-conformed to fit your head, since very few silk top hats have been made since French production largely ceased in the 1970s.

his inauguration in 1960, and then abandoned by Lyndon Johnson and all the presidents who followed. Alas, in spite of its storied history, the top hat has largely gone out of fashion. There are, of course a few exceptions, like the iconic top hat that Slash, the guitar player from Guns & Roses adopted as part of his persona. But what was once commonplace has now become a rarity. It is, of course, still possible to purchase a silk plush top hat, though you’ll likely be buying a reconditioned model, re-conformed to fit your head, since very few silk top hats have been made since French production largely ceased in the 1970s.

I’m not sure what, exactly, led to the demise of the top hat. Perhaps top hats were simply too much trouble to take care of, what with the need to find suitable places to store them wherever you went. Can you even imagine a gentleman walking onto an airplane with a top hat, and trying to find space in the overhead compartment to store it so that it wouldn’t be damaged? I think that our world today is, in a rather uncomfortable way, too crowded to allow for men wearing top hats. It’s too bad. I think they’re pretty cool. I can picture myself, swirling my cape, with a silver knobbed walking stick in one hand, doffing my top hat as I head off to take on the world….then, poof, the image evaporates as I remember that, most days, I wear my pajamas into my home office in the morning.

While

While  very mild turbulence. But everything changed when we made our approach to

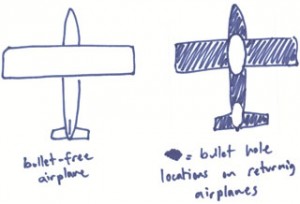

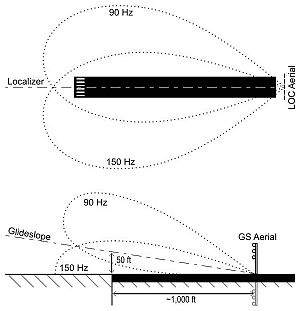

very mild turbulence. But everything changed when we made our approach to  When flying under IFR, once the plane is established on its final approach, it is guided by a highly sophisticated Instrument Landing System (ILS) which provides precision guidance to help the pilot get the aircraft properly aligned for a landing. [If you are interested, you can find out everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask about Instrument Landing Systems and how they work by clicking

When flying under IFR, once the plane is established on its final approach, it is guided by a highly sophisticated Instrument Landing System (ILS) which provides precision guidance to help the pilot get the aircraft properly aligned for a landing. [If you are interested, you can find out everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask about Instrument Landing Systems and how they work by clicking  The scarcity of decision triggers for contingency plans should seem surprising, given the difficulty, some would say the impossibility, of accurate predicting the flow of future events. But we are generally supremely overconfident about our plans, whether or not that confidence is justified. We also tend to disregard any evidence that would suggest that our plan is in trouble, so any contingency plans we may have made are rarely taken seriously. I’m not sure that any amount of pleading will improve that situation. In the meantime, I’m glad that we didn’t attempt an overly risky landing, and got down safe and sound, even if we were a few hours late. It’s a trade-off I’d make every time.

The scarcity of decision triggers for contingency plans should seem surprising, given the difficulty, some would say the impossibility, of accurate predicting the flow of future events. But we are generally supremely overconfident about our plans, whether or not that confidence is justified. We also tend to disregard any evidence that would suggest that our plan is in trouble, so any contingency plans we may have made are rarely taken seriously. I’m not sure that any amount of pleading will improve that situation. In the meantime, I’m glad that we didn’t attempt an overly risky landing, and got down safe and sound, even if we were a few hours late. It’s a trade-off I’d make every time.