I read something the other day that appealed to the techno-geek in me. It has to do with techniques for predicting technological progress. The go-to rule for predicting progress in the technology realm, at least what I always thought was The Rule, was attributed to Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel Corporation. The rule is commonly known as Moore’s Law. Moore’s law has been the benchmark measurement for technical progress in electronics for decades.

I read something the other day that appealed to the techno-geek in me. It has to do with techniques for predicting technological progress. The go-to rule for predicting progress in the technology realm, at least what I always thought was The Rule, was attributed to Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel Corporation. The rule is commonly known as Moore’s Law. Moore’s law has been the benchmark measurement for technical progress in electronics for decades.

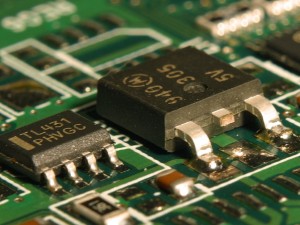

Moore’s Law was a prediction that the number of transistors the industry would be able to place on a computer microchip would double every year. While originally intended as a rule of thumb in 1965, it has become the guiding principle for the industry to deliver ever-more-powerful semiconductor chips at proportionate decreases in cost. In 1995, Moore updated his prediction to once every two years. The doubling of transistors on a chip translates to a doubling of computing power and so–it was believed– Moore’s law “explains” why people today can carry a computer in their pocket, the ever-present smartphone, that is far more powerful than the computers used to control the Apollo moon missions.. The rub is that, since Moore’s law applies only to electronics, it can’t be used to forecast technological progress in other areas.

Moore’s Law was a prediction that the number of transistors the industry would be able to place on a computer microchip would double every year. While originally intended as a rule of thumb in 1965, it has become the guiding principle for the industry to deliver ever-more-powerful semiconductor chips at proportionate decreases in cost. In 1995, Moore updated his prediction to once every two years. The doubling of transistors on a chip translates to a doubling of computing power and so–it was believed– Moore’s law “explains” why people today can carry a computer in their pocket, the ever-present smartphone, that is far more powerful than the computers used to control the Apollo moon missions.. The rub is that, since Moore’s law applies only to electronics, it can’t be used to forecast technological progress in other areas.

Researchers from the Santa Fe Institute now argue that a theory, proposed by Theodore Wright in 1936, called Wright’s law, is actually a better reflection of technological progress than is Moore’s law. In their working paper, “Statistical Basis for Predicting Technological Progress”, the Santa Fe Institute researchers detail how they looked at technological progress rates from 62 different technologies, including chemical compound manufacture, mechanical engineering, etc., and found key similarities. In effect, they found that economies of scale trump time in the race to drive down costs.

“Moore’s law says that costs come down no matter what at an exponential rate. Wright’s law says that costs come down as a function of cumulative production. It could be production is going up because cost is going down,” said Santa Fe Institute lecturer Doyne Farmer told The Futurist magazine in a recent interview.

More importantly, Wright’s law can be applied to a much wider variety of engineering areas, not just transistors. That will give technological forecasters a new way to measure and predict progress and cost for everything from airplane manufacturing (its original use in 1936) to the costs of building better photovoltaic panels, used to provide solar energy. This is what got me excited about Wright’s Law.

“It means that if investors or the government are willing to stimulate production, then we can bring the cost down faster. In the case of global warming, for instance, I think that a massive stimulus program has the potential to really bring the arrival date for having solar energy beat coal a lot sooner,” said Farmer.

This argument mirrors my own view, which was previously unsupported by scientific evidence, that if we are serious about America developing alternative energy resources, like solar power, we need some type of significant stimulus to production. The stimulus could take a number of forms. For example, a tax on fossil fuels would make alternatives, like solar, more cost competitive; and if fossil fuel and solar options were offered at the same price, I have to believe that the demand for solar would increase exponentially. If Wright’s Law holds true, the increased production, driven by demand, would have the happy result of lowering the cost of solar, making it even more attractive when compared to fossil fuels.

This argument mirrors my own view, which was previously unsupported by scientific evidence, that if we are serious about America developing alternative energy resources, like solar power, we need some type of significant stimulus to production. The stimulus could take a number of forms. For example, a tax on fossil fuels would make alternatives, like solar, more cost competitive; and if fossil fuel and solar options were offered at the same price, I have to believe that the demand for solar would increase exponentially. If Wright’s Law holds true, the increased production, driven by demand, would have the happy result of lowering the cost of solar, making it even more attractive when compared to fossil fuels.

Farmer and his colleagues are expanding their working paper into more expansive study that further details the relationship between costs and the rate of progress. In the interview with The Futurist, he indicated that he and his colleagues are trying to make solid, probabilistic forecasts for where costs for solar will be with and without stimulus, aas well as a probabilistic distribution of time frames for cost reductions that will occur with business-as-usual approach, compared to various stimulus scenarios.

I wish them luck.

I love it. Simple reasoning: increase demand, increase supply, see costs go down. The Chinese government has been using this model for years (albeit for exports), none-the-less the US can do so too. The Federal government is a massive purchaser of goods and services. If we mandate significant purchases of solar by the Feds, and offer significant tax credits to people and companies, demand and supply will follow.

Mandating solar purchases by the Federal government is an option, but not the only option. The key is to do something–anything–that makes solar purchases more of a no-brainer economically, rather than having to get a subsidy to make it work.