A number of years ago I attended a seminar on Power and Influence delivered by Charles Dwyer, a long-time faculty member at the Wharton School. Dr. Dwyer argued that organizations don’t have any life force, so they can’t have missions, values, visions goals objectives or purposes. Only PEOPLE can have these things, because only people have intellects. He went on to state that there is no such thing as Organizational Culture. In Dr. Dwyer’s view, the use of the term is a misapplication of an anthropological concept.

A number of years ago I attended a seminar on Power and Influence delivered by Charles Dwyer, a long-time faculty member at the Wharton School. Dr. Dwyer argued that organizations don’t have any life force, so they can’t have missions, values, visions goals objectives or purposes. Only PEOPLE can have these things, because only people have intellects. He went on to state that there is no such thing as Organizational Culture. In Dr. Dwyer’s view, the use of the term is a misapplication of an anthropological concept.

His argument was premised on the proposition that an organization is merely a tool utilized by humans to help further the pursuit of what they value. Thus, according to Dr. Dwyer:

“…an organization can no more have a mission, values or vision than a hammer or a wineglass can have objectives, goals or purposes.”

Perhaps, if you take a very highly filtered, mechanistic view of the term organization, limiting the scope of the concept to a narrow range of physical artifacts that represent aspects of on organization’s structure – such as organization charts, job descriptions, etc. – thinking of an organization as nothing more than a tool might make sense. Moreover, within the context of power and influence, the concept of ”organization as tool” might be effectively used to support the notion that power and influence have to be applied to human beings, as individual thinking and behaving entities, and can’t be effectively applied to an abstract entity like an organization.

In the end, though, this mechanistic view of organizations doesn’t work for me. I’ve been a part of organizations of various kinds my whole life — school classes, Boy Scout troops, Little League baseball teams, college fraternity, US Navy units, public companies and not-for-profits, the list could go on — and each of them had an influence on how I behaved. Something about each of the organizations almost compelled me to fall into line with a common set of behavioral norms, specific to that particular entity. These norms helped to define what the organization was all about. For lack of a better descriptor I have to call it the organization’s culture.

In some ways, culture to an organization seems to be like personality to an individual. Some organizations can be characterized as warm and caring while others are seen as cold and heartless. Some organizations are seen to be innovative and aggressive while others come across as stodgy and passive. Some organizations act carefully and professionally at all times, while others are so lackadaisical that it’s a wonder that they can stay in business.

Of course, in all of the above examples, you can argue that it is, in fact, the human beings that are a part of these organizations that are warm and caring, cold and heartless, innovative and aggressive, stodgy and passive, careful and professional, or lackadaisical. And you’d be correct. But there is something going on beneath the surface, some set of rules or constraints – mostly unwritten – that drives behavior of an organization’s members into a recognizable pattern. That, in my view, is organizational culture doing its work.

Unfortunately, the cultures that can be observed in organizations aren’t universally positive and functional. Negative and dysfunctional organizational cultures are so common that it isn’t worth the effort to list examples. Make up our own list if you need one. What I wonder about is how and why these undesirable cultures come about.

The best take of many observers is that cultures are like forts or castles. They don’t suddenly appear, fully formed out of the ether. They are built, a stone at a time, a beam at a time, a brick at a time, until the structure is completed. And the purpose is clear. Keep others out; protect those within. Given this view of organizational culture, it is no wonder that the mere idea of changing an organization’s culture is enough to send otherwise stalwart CEO’s into a quavering panic, anticipating an expensive and lengthy effort involving large-scale and long-term consulting engagements, mass meetings, sloganeering etc., all ultimately to no avail.

The best take of many observers is that cultures are like forts or castles. They don’t suddenly appear, fully formed out of the ether. They are built, a stone at a time, a beam at a time, a brick at a time, until the structure is completed. And the purpose is clear. Keep others out; protect those within. Given this view of organizational culture, it is no wonder that the mere idea of changing an organization’s culture is enough to send otherwise stalwart CEO’s into a quavering panic, anticipating an expensive and lengthy effort involving large-scale and long-term consulting engagements, mass meetings, sloganeering etc., all ultimately to no avail.

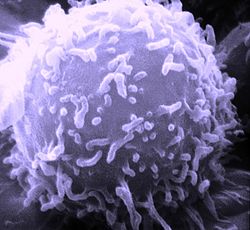

I have a different metaphor in mind; one that makes the idea of changing an organization’s culture significantly less daunting. Rather than viewing culture as the castle that preserves the system of behavior, I think of culture operating a lot like lymphocytes, the class of white blood cells that protect the body by surrounding, sequestering and removing threats [such as tumors and viruses] to the body’s continued functioning. In addition to these designated Culture Cops, there are, of course, many other elements that help protect the existing culture, but I think you get the idea; culture preservation is more about unseen elements than highly visible protective walls and battlements.

I have a different metaphor in mind; one that makes the idea of changing an organization’s culture significantly less daunting. Rather than viewing culture as the castle that preserves the system of behavior, I think of culture operating a lot like lymphocytes, the class of white blood cells that protect the body by surrounding, sequestering and removing threats [such as tumors and viruses] to the body’s continued functioning. In addition to these designated Culture Cops, there are, of course, many other elements that help protect the existing culture, but I think you get the idea; culture preservation is more about unseen elements than highly visible protective walls and battlements.

The culture of an organization works largely behind the scenes, invisible to the naked eye, with its Culture Cops patrolling and looking for intruders – those whose behavior doesn’t fit within the prevailing behavioral rules and strictures of the organization. [Of course, the Culture Cops don’t wear uniforms and badges designating their special roles. In most cases, they are simply helpful members of the organization who explain, “This is how we do things here” to aid newcomers in the process of adaptation and fitting in.]

Given this view, the simplest path* to changing an organization’s culture may lie in:

- first, defining what the “new” or “replacement” cultural aspects would be, in idiosyncratic, behavioral terms;

- then, identifying those aspects of the existing pattern of behavior within the organization that are or have become dysfunctional and should be changed;

- and, searching out the constraints that seem to bind the behavior into the undesirable pattern;

- followed by, identifying the levers necessary to shift the constraints as needed to create the new pattern; and

- finally, designing the smallest possible catalytic set of actions necessary to deliver the desired outcome.

[*This approach is based on my colleague Dr James Wilk’s groundbreaking work on Minimalist Intervention . You can learn more about Dr Wilk and Minimalist Intervention at www.interchangeassociates.com.]

So, when faced with the challenge of changing the castle of culture, consider laying aside the siege engines and instead, looking for the lymphocytes, and figuring out how to use them to do the work of culture change.

Dave, the organization that came to mind as I read your essay is The Church — or rather, my church. I’ve been in one where the fortress analogy was most appropriate. Fortunately we now attend one where I can see your alternate analogy as being more applicable.

Thanks for jump starting my brain thus morning.