Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit: wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad. This sentence is an example of a paraprosdokian.

Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit: wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad. This sentence is an example of a paraprosdokian.

Look the word up in your dictionary: “p-a-r-a-p-r-o-s-d-o-k-i-a-n.” If you can find it, let me know where you found it. I tried, and I can’t find it in any traditional dictionary, including the Oxford English Dictionary, which I rely on as my my trusted reference work for the meaning of words. I was able to find a definition in the Urban Dictionary, a web-based, online dictionary, originally intended as a dictionary of slang or cultural words or phrases not typically found in standard dictionaries, but now used to define any word or phrase. According to the Urban Dictionary, paraprosdokian is:

The term for a figure of speech in which a sentence or phrase has an unexpected or surprising ending. Often used for humorous effect, and thus heavily used by comedians.

I prefer the definition I found in Wikipedia:

A paraprosdokian /pærəprɒsˈdoʊkiən/ is a figure of speech in which the latter part of a sentence or phrase is surprising or unexpected in a way that causes the reader or listener to reframe or reinterpret the first part. It is frequently used for humorous or dramatic effect, sometimes producing an anticlimax. For this reason, it is extremely popular among comedians and satirists. Some paraprosdokians not only change the meaning of an early phrase, but they also play on the double meaning of a particular word.

According to Wikipedia, the word comes from the Greek “para“, meaning “against” and “prosdokia“, meaning “expectation”. Canadian linguist and etymology author William Gordon Casselman argues that, while the word is now in wide circulation, “paraprosdokian” (or “paraprosdokia”) is not a term of classical (or medieval) Greek or Latin rhetoric, but is a newly coined term from the late 20th-century. [It’s relatively recent introduction to the lexicon may serve to explain its absence from the O.E.D.] Other students of language argue that the term appears, albeit infrequently, in at least a few 19th century volumes, and may have actual roots in early Greek writing on rhetoric.

I’d certainly never heard of the word before, but encountered it in an email from a friend, who forwarded a list of twenty or so examples of this delightful figure of speech. Winston Churchill was apparently a fan of the paraprosdokian, though if Mr. Casselman is correct, Sir Winston would never have referred to these classic lines as such:

I’d certainly never heard of the word before, but encountered it in an email from a friend, who forwarded a list of twenty or so examples of this delightful figure of speech. Winston Churchill was apparently a fan of the paraprosdokian, though if Mr. Casselman is correct, Sir Winston would never have referred to these classic lines as such:

“A modest man, who has much to be modest about.” —Winston Churchill on Clement Atlee

“There, but for the grace of God, goes God.” —Winston Churchill about a pompous fellow politician.

“It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried.”

“Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.”

Here are my Top Ten Paraprodokians:

10. Everything comes to those who wait… except a cat.

10. Everything comes to those who wait… except a cat.

9. I’ve had a perfectly wonderful evening, but this wasn’t it. – Groucho Marx

8. Don’t argue with an idiot; he’ll drag you down to his level and beat you with experience.

7. I want to die peacefully in my sleep, like my grandfather, not screaming and yelling like the passengers in his car.

6. Light travels faster than sound; that’s why some people appear bright until you hear them speak.

5. If I agreed with you we’d both be wrong.

4. Some cause happiness wherever they go. Others, whenever they go. – Oscar Wilde

3. Always borrow money from a pessimist. He won’t expect it back.

2. We don’t stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing.

And my all-time favorite:

1. The difference between stupidity and genius is that genius has its limits. – Albert Einstein

What are some of your favorites?

My first encounter with the distinction between knowing how and knowing that came courtesy of my good friend and philosophical mentor

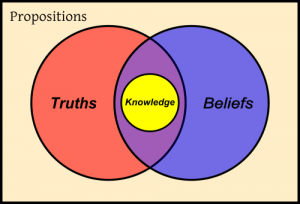

My first encounter with the distinction between knowing how and knowing that came courtesy of my good friend and philosophical mentor  Of course, the idea that we can know something, leads inevitably to the notion that there must be some category of things that we know, ergo, we have knowledge.

Of course, the idea that we can know something, leads inevitably to the notion that there must be some category of things that we know, ergo, we have knowledge.  Not to put too sharp of a point on the pencil, let me simply take a break here and note that these are B-I-G questions, and that philosophers have struggled with them for almost as long as people have been able to walk on the earth without spending every waking minute either looking for their next meal or trying to avoid being some hungry critter’s next meal; and they will still be arguing about the same questions when our Sun explodes into supernova and smashes our planet and everything on it into dust particles that drift to the outer reaches of our galaxy.

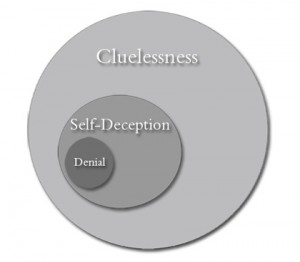

Not to put too sharp of a point on the pencil, let me simply take a break here and note that these are B-I-G questions, and that philosophers have struggled with them for almost as long as people have been able to walk on the earth without spending every waking minute either looking for their next meal or trying to avoid being some hungry critter’s next meal; and they will still be arguing about the same questions when our Sun explodes into supernova and smashes our planet and everything on it into dust particles that drift to the outer reaches of our galaxy. Back to current reality, the story about Notre Dame football player Manti Te’o and his “fictional” girlfriend certainly appears to have some markers of self-deception. When you read about the young linebacker’s story, you can’t help but wonder, “How could he be so clueless?”

Back to current reality, the story about Notre Dame football player Manti Te’o and his “fictional” girlfriend certainly appears to have some markers of self-deception. When you read about the young linebacker’s story, you can’t help but wonder, “How could he be so clueless?” Considering how commonly this word is used, or is at least being considered for use, you might, like me, think that it has been in common usage [adjusted for changes in the vernacular] since the time of Ugg and Mug the cavemen. Not so, according to

Considering how commonly this word is used, or is at least being considered for use, you might, like me, think that it has been in common usage [adjusted for changes in the vernacular] since the time of Ugg and Mug the cavemen. Not so, according to  But perhaps there is an answer to the problem of defining an asshole, beyond the “I know one when I see one” non-definition. To the rescue comes

But perhaps there is an answer to the problem of defining an asshole, beyond the “I know one when I see one” non-definition. To the rescue comes  For myself, I don’t really want to understand assholes; since there is almost no hope that they will ever understand me. I guess the best strategy is to avoid them as much as possible, and try not to let them get under my skin when I do, inevitably, meet up with yet another asshole. And of course, do my best to keep my own asshole behavior to an absolute minimum.

For myself, I don’t really want to understand assholes; since there is almost no hope that they will ever understand me. I guess the best strategy is to avoid them as much as possible, and try not to let them get under my skin when I do, inevitably, meet up with yet another asshole. And of course, do my best to keep my own asshole behavior to an absolute minimum.