At a press conference on June 6, 2002 at NATO headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, in response to a question about the quality of intelligence about terrorism and weapons of mass destruction, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld delivered his now-famous quote about “unknown unknowns:”

“There are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say there are things that we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.”

Rumsfeld was talking about military intelligence, but the concept extends to every realm of life. None of us would argue with Rumsfeld, because we realize that there are lots of things we don’t know. These are our “known unknowns.”

I don’t know the distance from Laguna Niguel, California to Phuket, Thailand [photo at left], and I know that I don’t know it; but I can easily look it up. [I just now typed “Distance from Laguna Niguel, CA to Phuket, Thailand” into Google Search and learned that the distance is 8,743.9 miles–14,071.9 kilometers if you use the metric system of measurement–so I guess it’s no longer a known unknown.] Of course, there are millions of other things I don’t know, and I know I don’t know them; but I’m not clueless about them. With some diligence I can find out about practically any known unknown.

I don’t know the distance from Laguna Niguel, California to Phuket, Thailand [photo at left], and I know that I don’t know it; but I can easily look it up. [I just now typed “Distance from Laguna Niguel, CA to Phuket, Thailand” into Google Search and learned that the distance is 8,743.9 miles–14,071.9 kilometers if you use the metric system of measurement–so I guess it’s no longer a known unknown.] Of course, there are millions of other things I don’t know, and I know I don’t know them; but I’m not clueless about them. With some diligence I can find out about practically any known unknown.

Many tasks in life contain uncertainties that we know about—our “known unknowns.” While these challenges exist as potential problems, they are at least problems that we can be on the lookout for, prepare for, insure against, and, when we are lucky, head off at the pass. The challenge is, in most cases, to frame and ask the right questions.

But what about the unknown unknowns? How can you find an answer when you don’t know the question? Or worse, you don’t even realize that there is a question you should be asking. In engineering, the term “unk-unk” was coined to describe something, such as a problem, that has not been and could not have been imagined or anticipated, much like the unanticipated happenings described by Nassim Nicholas Talib in his 2007 best-seller, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. We simply aren’t very good at anticipating the unexpected. Unfortunately that fault doesn’t slow us down the least bit when it comes to making predictions about the future–we expect tomorrow to be much like today.

But what about the unknown unknowns? How can you find an answer when you don’t know the question? Or worse, you don’t even realize that there is a question you should be asking. In engineering, the term “unk-unk” was coined to describe something, such as a problem, that has not been and could not have been imagined or anticipated, much like the unanticipated happenings described by Nassim Nicholas Talib in his 2007 best-seller, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. We simply aren’t very good at anticipating the unexpected. Unfortunately that fault doesn’t slow us down the least bit when it comes to making predictions about the future–we expect tomorrow to be much like today.

It would seem that if the hallmark of an intelligent person is knowing what we don’t know, then most of us aren’t very intelligent. The Dunning-Kruger effect, which I wrote about in Part II of this three-part post series, suggests that we are perhaps hopelessly confounded by our own cluelessness. Even if I were just the most honest, impartial person that I could be, I would still have a problem — namely, when my knowledge or expertise is imperfect, I really don’t know it. Left to my own devices, I just don’t know it.

Cluelessness, in general, seems to shape our lives in ways we are not even aware of. We tend to do what we know and fail to do what we have no idea about. As a result, cluelessness profoundly directs the paths we take in life. We often come up with answers to problems that seem to be okay, but are not the best solutions. We don’t come up with better solutions because we are not aware that they even exist. We fail to reach our potential as professionals, friends, parents and people simply because we aren’t aware of what is possible.

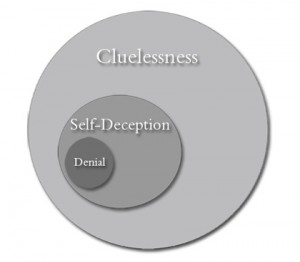

In an interview with Errol Morris, excerpted in Morris’ essay “The Anosognosics Dilemma,” David Dunning described the relationship of Cluelessness, Self-Deception and Denial as sets in a Venn diagram, where:

In an interview with Errol Morris, excerpted in Morris’ essay “The Anosognosics Dilemma,” David Dunning described the relationship of Cluelessness, Self-Deception and Denial as sets in a Venn diagram, where:

“Cluelessness is clearly the biggest circle, in that there is so much knowledge and expertise that lies outside everybody’s personal cognitive event horizon. People can be clueless in a million different ways, even though they are largely trying to get things right in an honest way. Deficits in knowledge, or in information the world is giving them, just leads people toward false beliefs and holes in their expertise.Psychologists over the past 50 years have demonstrated the sheer genius people have at convincing themselves of congenial conclusions while denying the truth of inconvenient ones. You can call it self-deception, but it also goes by the names rationalization, wishful thinking, defensive processing, self-delusion, and motivated reasoning. There is a robust catalogue of strategies people follow to believe what they want to, and we research psychologists are hardly done describing the shape or the size of that catalogue. All this rationalization can lead people toward false beliefs, or perhaps more commonly, to tenaciously hang on to false beliefs they should really reconsider. Denial, to a psychologist, is a somewhat knuckle-headed technique in self-deception, and it is to merely deny the truth of something someone does not want to confront.

Asked by Morris about the possibility of escaping from what Morris called our “prison of cluelessness,” Dunning suggested that the road to self-insight runs through other people, so getting good feedback is critical. You need to ask yourself whether the world is telling you good things; whether the world is rewarding you in ways you would expect a competent person to be rewarded. If you watch other people, you often find there are different ways to do things; there are better ways to do things. You want to surround yourself with smart, competent people, so you can compare what you do with what they do. Maybe you’ll observe that you aren’t as good as you thought you were, that you have something to work on.

Unfortunately, as we learned in the previous post, the less competent you happen to be, the less likely you are to be able to see that what others do is superior to what you do. If you are at the bottom of the competency totem pole, and you see what people at the top actually do, you won’t get it. You won’t realize that what those other people are doing is superior to what you’re doing.

Unfortunately, as we learned in the previous post, the less competent you happen to be, the less likely you are to be able to see that what others do is superior to what you do. If you are at the bottom of the competency totem pole, and you see what people at the top actually do, you won’t get it. You won’t realize that what those other people are doing is superior to what you’re doing.

And what if the the people that you’ve picked to give you feedback or advice are, themselves, incompetent nincompoops. If you lack the ability to discriminate between nincompoops and non-nincompoops, between good advice and bad advice, between what makes sense and what doesn’t make sense, the feedback will do you no good.

I suspect that we’re doomed to be clueless. But cluelessness provides it’s own saving grace–we’ll never know how bad off we really are!

Fabulous – I didn’t know how prevalent cluelessness was. Now I know why:) At Successful Transition Planning Institute, we show Baby Boomer business owners some areas to educate themselves to reduce unknown unknowns.

Paul,That’s the biggest reason I appreciate the work you and Jack do. You help people become aware of how much they don’t know, and help them deal with that “knowledge-about-what-I-don’t-know” without panicking.

I am hugely surprised that this topic has not been given more attention, because for me it seems transformative, a gateway to a region I’m still thinking about. It’s a little embarrassing to admit that knowing about the D-K effect alone was not enough to engage my imagination, but it’s gonna be a couple of days yet, I’m guessing, before I achieve perfection…

In the meantime, some humor from “The Anosognosic’s Dilemma”:

“I would write more, and there’s probably a lot more to write about, but I haven’t a clue what that all is.” – David Dunning to Errol Morris

Errol Morris fancies a version of Adam and Eve’s expulsion in which God gets remorseful for how badly he’s screwing A & E, so relents a bit: “Yes, things will be bad out there, but I’m giving you self-deception so you’ll never notice.”

Jim, in two-and-a-half years of writing this blog,this is the most incredible comment I’ve received. I’m curious: How did you find this piece?

Uh oh, Dave, I have a bad feeling in the pit of my pit, or somewhere, because I inadvertently stumbled across your response to me about one of your posts re. David Dunning, anosognosia, etc. I have this expectation that if anyone responds to something I wrote, I will get a note in my email that says so; but if I got one about this I missed it. So glad I found it at last, although if an old man (75) could blush, I would, because I was so flattered by your note. And if you thought about it at all, you must have suspected me of being a terribly rude bastard for failing to reply.

After all this time, I can only guess at why I found your blog in the first place, but I imagine I was Googling dunning or anosognosia, because I’ve become obsessed with them. My primary obsession all my life, though, has been human behavior, and I find myself using the Dunning ideas in my thinking – for example, I imagine a scale for compassion where Paul Ryan suffers from a significant deficit – but doesn’t know it. This leads me to demand of myself that I not hate him, since he can’t help it. But I hate him anyhow. This puzzles me.

I’m also vitally interested (because I decided not to say “obsessed” again, since it seems to me one should not have too many obsessions) with leadership, including the Wikipedia-style idea of un-led groups; and the feminine/egalitarian style of non-aggressive leadership which I, as an “androgyne” have practiced and preached…

I hope you’re not offended by my lefty philosophy. I find that I’ve run all the way to the pink end of the lib/con spectrum, and recognize it as my natural resting place. You can imagine that I was not a natural fit as an IT director in a Dun & Bradstreet company!

I’m sending this as a reply to your blog post (which has by now a record-breaking longevity). I will send a copy of my blathering about the Dilemma to your email address directly.

I’m in Capistrano, lived in Laguna Niguel (near Alicia & Niguel Rd.) for 12 years. We owned a pet supply store to the right of Sprouts called Pet Junction, which succeeded despite the PetSmart up the hill! I think we should get a cup (Corner Bakery?) and could probably sustain one another’s interest at least long enough to drink it!

Jim,

Now that we’ve been corresponding, it seems odd to me to find your comment whiling away on my blog, waiting to be “moderated.” I literally stumbled over it this evening when I decided to look at my blog and found your reply [The longest-ever reply to one of my posts].

I look forward to having a cup of Joe with you soon, but it will probably have to wait until I return from Spain in mid-May. I’ll be in touch.