We all know what it’s like to get really STUCK when working on an issue or a problem. Sometimes when it happens to me, I feel like I’m stalling out, as if I had been digging a hole and hit a big rock. The rock is too heavy to move; too large to get around it. It occurs to me that I should try to feel what’s it like when I actually touch the rock. Maybe even lie down on it.

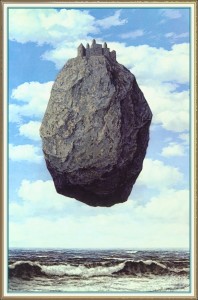

But I don’t think that will work. I think the rock that is holding me back is another world unto itself. [The image conjured by Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte’s The Castle of the Pyrenees always comes to mind when I start on this particular chain of thought.] I can’t break the rock up into pieces or control it in any meaningful way. Maybe I should try to understand it. To do that, though, I have to make myself small. Very small. So small that I can penetrate the world that is the rock, almost swim inside the world that is the rock. I have to get inside and explore it.

But I don’t think that will work. I think the rock that is holding me back is another world unto itself. [The image conjured by Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte’s The Castle of the Pyrenees always comes to mind when I start on this particular chain of thought.] I can’t break the rock up into pieces or control it in any meaningful way. Maybe I should try to understand it. To do that, though, I have to make myself small. Very small. So small that I can penetrate the world that is the rock, almost swim inside the world that is the rock. I have to get inside and explore it.

Getting bigger doesn’t help. Backing away to “get perspective” doesn’t help. There’s a world there that simply isn’t visible from where I stand, shovel in hand, digging the hole. To make progress, I’ll need to get make myself small, literally get inside the problem world that has me stuck, so I can finally see what’s really going on, in all of its idiosyncratic detail. It may not be only the devil that’s in the details; the answer may also be hiding in the details.

Maybe this approach will work for you. Maybe not. Maybe some “problems” are just not amenable to solutions. Perhaps, as William Burroughs wrote:

“There are certain things human beings are not permitted to know — like what we’re doing.”

I prefer to think that Burroughs had it wrong, and the quote, attributed to Albert Einstein, gives the proper guidance when you get stuck:

“The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them.”

I think being stuck is rarely something that can be relieved on one’s own efforts as “the same level of thinking” or at least the same set of tacit assumptions is all one has at hand. It is the thinking that, for example, has us believe that our path is blocked by a huge rock and pondering what to do about it.

Other thinking might wonder what brought us to that particular path with the huge rock in it. It may be that the rock—taken at face value—is a signal for “don’t take this path” as it is the wrong or most difficult way. It may be the blocked path is an attempted solution we are trying to get to work, despite evidence that it won’t. Then the issue itself has become forgotten as we try to figure out how to get around such daunting obstacles. And it may be as you suggest that, on closer examination, the rock isn’t quite as solid as it appears or even that you can use the rock in some way to further your progress.

However, these options seem frivolous as one sits there stuck, convinced the rock is blocking the only path and wondering what to do about it.

I know the answer. When faced eye-to-eye with the Rock, you simply move to the other side of said Rock. You need to see if from another perspective. What appears to be a block is not a block at all, but an invitation to change perspective. If you miss the opportunity, you miss much more than simply being stuck.

Yes. You gave it to me.