While Albert Hammonds was almost correct in his 1972 song, It Never Rains In Southern California, that doesn’t mean the sun is always shining. We call our own special brand of fog marine layer. It’s a dense layer of fog that rolls in off the ocean in Southern California, drawn in by the warm air over the desert, pulling cold damp air from over the Pacific Ocean. When the desert air warms up in the Spring, and the ocean water is still very cold, the resulting fog layer lasts late into the morning, and returns early in the evening, giving rise to the phrases “Gray May” and “June Gloom” to describe the weather pattern. After a few years you get used to it, even if you don’t like it. After all, it’s simply fog, and it’s nothing more than a minor inconvenience–unless you are trying to land an airplane. Then it can be very scary.

While Albert Hammonds was almost correct in his 1972 song, It Never Rains In Southern California, that doesn’t mean the sun is always shining. We call our own special brand of fog marine layer. It’s a dense layer of fog that rolls in off the ocean in Southern California, drawn in by the warm air over the desert, pulling cold damp air from over the Pacific Ocean. When the desert air warms up in the Spring, and the ocean water is still very cold, the resulting fog layer lasts late into the morning, and returns early in the evening, giving rise to the phrases “Gray May” and “June Gloom” to describe the weather pattern. After a few years you get used to it, even if you don’t like it. After all, it’s simply fog, and it’s nothing more than a minor inconvenience–unless you are trying to land an airplane. Then it can be very scary.

Flying home to Orange County, California from San Francisco on Thanksgiving weekend, we were thrilled to be upgraded to first class on a United 757-200 jet, even for the brief, 60-minute flight south. We’d spent an enjoyable few days with our daughters and son-in-law, and were ready to get home and begin preparing the house for the holidays. When we took off shortly after 9:00 p.m., we drank a glass of red wine, then buried our noses in our eReaders [Kindle for me, iPad for my wife]. I calculated that we’d be home around 10:30, barring any delays picking up our luggage at baggage claim. All was right with the world, at least for the moment.

The flight to Orange County had been relatively uneventful, with only a few minutes of  very mild turbulence. But everything changed when we made our approach to John Wayne Airport. As the airplane descended below 2,000 feet on final approach to the runway, we entered an area of very thick fog, so dense that I couldn’t see a single light shining up from the streets of Irvine, the crowded city where John Wayne Airport is located. I searched for the 405 freeway, which runs perpendicular to the runways at John Wayne, but literally couldn’t see even one pair of headlights–nothing but fog.

very mild turbulence. But everything changed when we made our approach to John Wayne Airport. As the airplane descended below 2,000 feet on final approach to the runway, we entered an area of very thick fog, so dense that I couldn’t see a single light shining up from the streets of Irvine, the crowded city where John Wayne Airport is located. I searched for the 405 freeway, which runs perpendicular to the runways at John Wayne, but literally couldn’t see even one pair of headlights–nothing but fog.

Even the noise from the aircraft’s engines didn’t sound right to my ears; I’d made that landing over two hundred times in the past fifteen years, and this definitely sounded different. Then, at last, the runway lights came into view as we appeared to be no more than 100 feet or so from the ground, but instead of landing the aircraft, the captain powered up the engines and took us back up to a safe altitude. The First Officer apologized over the intercom, and advised that we were going to circle around and make a second attempt to land the plane. If we couldn’t get down at John Wayne, we’d divert to Ontario, CA Airport, about 40 miles further inland.

Around we went, and the second attempt led to a similar result–my wife clenching the armrests and bracing for a crash, but too much fog to see the runway clearly, so back up in the air we went. Surprisingly, the First Officer announced we were going to make a third attempt, since the visibility through the fog seemed to have improved slightly from the first to the second attempt. This time, passengers throughout the cabin seemed to be either hyper-alert or quietly resigned to their fates, but–much like in the movie “Groundhog Day,” the pilots started the approach to the runway, then pulled up and flew away, finally landing at Los Angeles International Airport around 11:00 p.m. I won’t bore you with the details of our long wait for the airline-provided bus to take us the 40 miles back to John Wayne airport, where got our car and drove home through the dense fog, arriving tired and emotionally depleted around 2:00 a.m.

Okay, it was a bit unsettling and a lot annoying, but we were safe. We landed safely, in spite of the fog, even if the plane didn’t arrive at the airport we expected. Most importantly, it was not an accident [no pun intended] that our landing happened the way it did. The entire landing process was guided by the FAA’s Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), a set of regulations that dictate how aircraft are to be operated when the pilot is unable to navigate using visual references–exactly the situation we encountered that night at John Wayne Airport in Orange County.

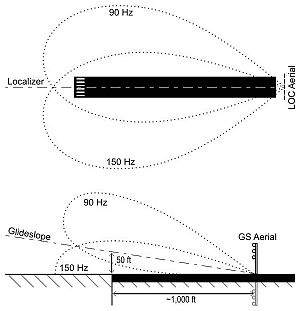

When flying under IFR, once the plane is established on its final approach, it is guided by a highly sophisticated Instrument Landing System (ILS) which provides precision guidance to help the pilot get the aircraft properly aligned for a landing. [If you are interested, you can find out everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask about Instrument Landing Systems and how they work by clicking here.] The pilot is not permitted to descend below a specified minimum “decision altitude” unless the visibility requirement is met and the pilot has the required visual references in sight for the runway where he intends to land. The decision altitude will vary, depending upon the runway length and location, and the capabilities of the specific aircraft. At 5,701 feeet, the runway at John Wayne is the shortest of any major airport in the United States. Accordingly, the decision altitude for John Wayne is set at 200 feet, the highest minimum decision altitude under IFR.

When flying under IFR, once the plane is established on its final approach, it is guided by a highly sophisticated Instrument Landing System (ILS) which provides precision guidance to help the pilot get the aircraft properly aligned for a landing. [If you are interested, you can find out everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask about Instrument Landing Systems and how they work by clicking here.] The pilot is not permitted to descend below a specified minimum “decision altitude” unless the visibility requirement is met and the pilot has the required visual references in sight for the runway where he intends to land. The decision altitude will vary, depending upon the runway length and location, and the capabilities of the specific aircraft. At 5,701 feeet, the runway at John Wayne is the shortest of any major airport in the United States. Accordingly, the decision altitude for John Wayne is set at 200 feet, the highest minimum decision altitude under IFR.

From the pilot’s standpoint, the decision process was very straightforward. He couldn’t establish satisfactory visual references, so, at 200 feet altitude, he aborted the landing at John Wayne, and pulled away to try again, and again, and yet again, finally diverting to LAX, with much longer runways, ranging from 10, 285 to 12,091 feet. Plan A was always, of course, to land at John Wayne. But the decision to go to Plan B– the contingency plan to abort the landing and try again or divert to another airport–wasn’t left to the judgment of the pilot. It was automatic, triggered by the failure to see the runway lights from at or above 200 feet.

When you think about it, it is surprisingly difficult to come up with other examples of an automatically triggered Plan B, especially in the business world. (If you can come up with some good business examples of the automatically triggered contingency plan, please send a Comment and share them.) All too often there is only Plan A. Moreover, when there is a contingency plan, it’s not at all clear when to abort or give up on Plan A and activate Plan B. No specific decision rule exists to tell the business leader that it is time to put the contingency plan into operation, before it is too late. Left to individual judgment, too many times Plan B isn’t activated in time, and the business crashes.

The scarcity of decision triggers for contingency plans should seem surprising, given the difficulty, some would say the impossibility, of accurate predicting the flow of future events. But we are generally supremely overconfident about our plans, whether or not that confidence is justified. We also tend to disregard any evidence that would suggest that our plan is in trouble, so any contingency plans we may have made are rarely taken seriously. I’m not sure that any amount of pleading will improve that situation. In the meantime, I’m glad that we didn’t attempt an overly risky landing, and got down safe and sound, even if we were a few hours late. It’s a trade-off I’d make every time.

The scarcity of decision triggers for contingency plans should seem surprising, given the difficulty, some would say the impossibility, of accurate predicting the flow of future events. But we are generally supremely overconfident about our plans, whether or not that confidence is justified. We also tend to disregard any evidence that would suggest that our plan is in trouble, so any contingency plans we may have made are rarely taken seriously. I’m not sure that any amount of pleading will improve that situation. In the meantime, I’m glad that we didn’t attempt an overly risky landing, and got down safe and sound, even if we were a few hours late. It’s a trade-off I’d make every time.

Great post Dave, sorry you had to go through it though.

I asked this of friends a couple years ago. The owners had a really good business, franchisor of retail stores, very profitable for 20 years. The grown kids were in law school or B-school. They had hopes the B-school child would enter the business and eventually become CEO. One problem: the student was learning about MUCH more interesting business models than retail. I said the them, “so what you’re telling me is that (x) discovered that mom and dad’s business wasn’t so sexy anymore”. They laughed and said yes. When I asked, “so what’s your Plan B”, I was met with dead silence. I hope it works out for them – good people. But it’s so unnecessary with some good planning.

I hate it when you hit the nail squarely on the head.