At the end of the summer between my sophomore and junior years in college, along with seven other 19- and 20-year old, testosterone-overloaded running mates from the Pittsburgh suburb where I grew up, I headed for the Jersey Shore. We piled into two cars and, armed with swim trunks, sandals, a couple of t-shirts, a few hundred dollars, and, most importantly some fake ID so we could buy beer, headed for Ocean City, New Jersey, arriving early on a Saturday afternoon, planning to stay for two weeks, get even darker tans, maybe meet some cute girls, and pretty much have a two week, end-of-Summer party. It was a great plan, and things were looking really good for us when we got the keys to the third-floor apartment we’d rented a few blocks from the beach, and found out that right next door was an extended family from Philadelphia–including a few cute teenage girls–spending the month of August in Ocean City. The trip had a sad ending when, only a week into our stay, after a much-too-noisy party, lubricated by cheap wine and cheaper beer, we were asked by the Ocean City police to “leave their quiet, little town and never return.”

At the end of the summer between my sophomore and junior years in college, along with seven other 19- and 20-year old, testosterone-overloaded running mates from the Pittsburgh suburb where I grew up, I headed for the Jersey Shore. We piled into two cars and, armed with swim trunks, sandals, a couple of t-shirts, a few hundred dollars, and, most importantly some fake ID so we could buy beer, headed for Ocean City, New Jersey, arriving early on a Saturday afternoon, planning to stay for two weeks, get even darker tans, maybe meet some cute girls, and pretty much have a two week, end-of-Summer party. It was a great plan, and things were looking really good for us when we got the keys to the third-floor apartment we’d rented a few blocks from the beach, and found out that right next door was an extended family from Philadelphia–including a few cute teenage girls–spending the month of August in Ocean City. The trip had a sad ending when, only a week into our stay, after a much-too-noisy party, lubricated by cheap wine and cheaper beer, we were asked by the Ocean City police to “leave their quiet, little town and never return.”

But this isn’t really a story about a crazy summer trip to the Jersey Shore. It’s about “sauce,” more specifically, the tomato-based, red sauce typically associated  with Italian pasta dishes. Unless, that is, you’re from certain parts of New Jersey or Philadelphia, or possibly Long Island, in which case it’s about “gravy.”

with Italian pasta dishes. Unless, that is, you’re from certain parts of New Jersey or Philadelphia, or possibly Long Island, in which case it’s about “gravy.”

You see, the day before that ill-fated party, we were invited to dinner with the girls next door. Their moms cooked up a huge pot full of spaghetti. Spaghetti without a good pasta sauce is nothing more than a plateful of noodles, so, when the crowd settled around the dining room table with mounds of spaghetti heaped on our plates, the male crew from Pittsburgh was confused when one of the girls asked us to pass her the gravy. We all started looking around for a dark brown, thick liquid on the table, since that’s what “gravy” was for us–the beef flavored stuff you poured into the little well you made in the center of a heap of mashed potatoes. Suffice it to say that the confusion ended when she reached across the table for the bowl filled with what to us unknowing Pittsburgh boys was a nice tomato “sauce” with lots of ground meat that was, in fact, the gravy that the Jersey Girl was asking for.

It was almost as if they were speaking a different language. One of us would point at the bowl of red stuff and say “sauce.” The girls would say, “No, it’s gravy.” And “sauce/gravy” wasn’t the only situation where we used different words to label the very same thing. They called carbonated beverages “soda;” to us it was always “pop” [probably a shortened form of “soda pop” another term often used to name any carbonated drink that wasn’t a Coke]. We all had a big laugh over it.

It was almost as if they were speaking a different language. One of us would point at the bowl of red stuff and say “sauce.” The girls would say, “No, it’s gravy.” And “sauce/gravy” wasn’t the only situation where we used different words to label the very same thing. They called carbonated beverages “soda;” to us it was always “pop” [probably a shortened form of “soda pop” another term often used to name any carbonated drink that wasn’t a Coke]. We all had a big laugh over it.

Remembering this story got me to thinking about how we can get tied up in knots over words. How often do we simply assume that other people know exactly what we mean when we say something? But then it turns out that the words or phrases we use mean something very, very different to them, and the outcome isn’t the sort of happy ending in the Gravy vs. Sauce story. It’s almost always the result of a failure to clearly and specifically describe the outcome we desire; instead, taking a shortcut and using an abstraction rather than a specific description. Most of the time we don’t even realize we’re using an abstraction, because it feels so natural, and it’s easy. We ask for a “ham and cheese sandwich,” when the clear picture in our mind is 5 ounces of thinly shaved honey-baked ham and two slices of Swiss cheese served on thinly-sliced pumpernickel rye bread with Dijon mustard on one slice of bread and mayonnaise on the other.

I see it happen all of the time in my consulting work. One example: A client is looking to hire someone who has “intelligence, energy, and integrity,” but is hard pressed to describe, in behavioral terms, exactly what he would be looking for the person to do in carrying out her job responsibilities, then winds up hiring someone who is alert and personable, but finds out three months later that she deals with difficult situations by caving in to unreasonable demands and compromising company policies. Ooops!

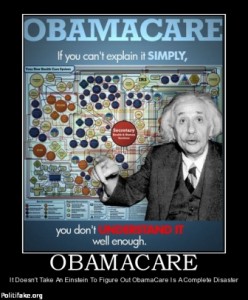

In politics, reliance on abstraction is taken to extremes. Consider how the term “ObamaCare” [a phrase originally coined by its opponents to denigrate The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which, along with the Healthcare and Education Reconciliation Act amendment, provided a sweeping overhaul of the U.S. healthcare regulatory environment ]” is used. Depending on your position on the Conservative/Liberal spectrum, you either praise ObamaCare or condemn it. Yet most of us don’t really have a clear idea of exactly what ObamaCare is or tries to do. Considering that the legislation runs to hundreds of mind-numbing pages of definitions and descriptions, our lack of clear understanding is understandable. But the fact remains that we all too often readily take a strong a position on something that we know about only in a very abstract sense.

In politics, reliance on abstraction is taken to extremes. Consider how the term “ObamaCare” [a phrase originally coined by its opponents to denigrate The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which, along with the Healthcare and Education Reconciliation Act amendment, provided a sweeping overhaul of the U.S. healthcare regulatory environment ]” is used. Depending on your position on the Conservative/Liberal spectrum, you either praise ObamaCare or condemn it. Yet most of us don’t really have a clear idea of exactly what ObamaCare is or tries to do. Considering that the legislation runs to hundreds of mind-numbing pages of definitions and descriptions, our lack of clear understanding is understandable. But the fact remains that we all too often readily take a strong a position on something that we know about only in a very abstract sense.

I suppose this is simply another example of how our pattern-recognition and pattern-matching skills, especially as applied to abstract descriptions, can be a double-edged sword. They help us swiftly deal with the astounding complexity of life-in-general without reducing us to madness, while at the same time denying us the ability to understand and richly experience the immensely satisfying detail of our lives .