I had been planning to write an article about stereotypes, and recently started wondering about the word “stereotype.” I had this idea in mind that the concept was somehow warped, since when I think of stereo-anything, [e.g. stereophonic speakers, stereoscopic viewing] it implies to me that there is a duality or multiplicity of perspectives being brought into play. That certainly is not the case with the common usage of the term today, where we use it to mean a popular belief about specific types of individuals.

I had been planning to write an article about stereotypes, and recently started wondering about the word “stereotype.” I had this idea in mind that the concept was somehow warped, since when I think of stereo-anything, [e.g. stereophonic speakers, stereoscopic viewing] it implies to me that there is a duality or multiplicity of perspectives being brought into play. That certainly is not the case with the common usage of the term today, where we use it to mean a popular belief about specific types of individuals.

So, before I dove into the concept of stereotypes, I took a detour into the etymology of the word? I was fascinated to learn that the term — derived from the Greek “stereos” [meaning firm or solid] and “typos” [meaning impression] thus solid impression — was invented around the end of the 18th century by Firmin Didot, a noted French printer and engraver.

In the printing world, stereotypes are metal printing plates, made by locking the type columns of a complete page in a form and molding a matrix, or mat, of papier-mache or similar material to it; the dried mat is used as a mold to cast the stereotype from hot metal. A stereotype plate is much stronger and more durable under a press run than would be a composed page of movable type. Didot’s invention revolutionized the book trade with its ability to produce cheap editions of books. In a fascinating coincidence [maybe not so much of a coincidence?], “cliche” is the French word for the actual printing surface of the stereotype plate. Of course, it,too, has a much different meaning in modern English.

The first usage of the word “stereotype” in the English language appears around 1850, with the meaning, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “image perpetuated without change.” But the more common modern meaning of the word — the metaphor of “pictures in our heads” — was coined in the 1922 book, Public Opinion, by American journalist, media critic and philosopher Walter Lippmann.

Explaining the inevitability, due to cognitive limitations, of the application of an evolving catalog of general stereotypes to a complex reality, Lippman wrote:

“For the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance. We are not equipped to deal with so much subtlety, so much variety, so many permutations and combinations. And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it.”

Of course, stereotyping is not limited to cultures or environments, but is also applied to people. In his book, Social Inequality: Forms, Causes and Consequences, sociologist Charles E. Hurst has offered, further, that:

“One reason for stereotypes is the lack of personal, concrete familiarity that individuals have with persons in other racial or ethnic groups. Lack of familiarity encourages the lumping together of unknown individuals.”

Another theory as to why people stereotype is that it is too difficult to take in all of the complexities of other people as individuals. Even though stereotyping is inexact, it can be an efficient way to mentally organize large blocks of information. Our ability to detect patterns and categorize is an essential human capability that enables us to simplify, predict, and organize our world. Assigning general group characteristics to members of that group saves time and satisfies the need to predict the social world in a general sense. Of course, once we have sorted and organized everyone into tidy categories, we have to deal with another of our human tendencies – avoiding processing new or unexpected information about each individual.

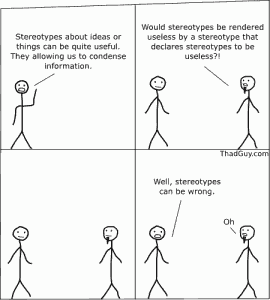

Not unexpectedly for generations like ours that have grown up during the eras of civil rights, women’s rights and, more recently, gay and lesbian rights, we have been taught to believe that stereotypes are largely negative and destructive. Yet, it is also a stereotype that stereotypes are inaccurate, resistant to change, overgeneralized, exaggerated, and destructive. Such a belief, however, is not founded on empirical social science research, which instead shows that stereotypes are often accurate and that people do not rely on stereotypes when relevant personal information is available.

Not unexpectedly for generations like ours that have grown up during the eras of civil rights, women’s rights and, more recently, gay and lesbian rights, we have been taught to believe that stereotypes are largely negative and destructive. Yet, it is also a stereotype that stereotypes are inaccurate, resistant to change, overgeneralized, exaggerated, and destructive. Such a belief, however, is not founded on empirical social science research, which instead shows that stereotypes are often accurate and that people do not rely on stereotypes when relevant personal information is available.

What are we to make of all of this? It seems that stereotypes can be helpful in some circumstances, but damaging and destructive in others. Perhaps an important component of anyone’s developing wisdom is the ability to distinguish between useful stereotypes and harmful stereotypes.

Which brings us off of the detour and back on to the point of this article. One type of stereotyping is, for me, particularly worrisome – stereotyping yourself. The concept of self-stereotyping is a fairly new one in the social sciences, but in its simplest form it describes a process whereby a person comes to see herself in a way consistent with stereotypes about her in-group. For example, a person who works in sales may begin to identify with the stereotype of “sales people,” and adopt behaviors and beliefs that are commonly held to be stereotypical of people in sales [e.g., extroversion; focus on people or personalities, rather than data; preference for working with others versus working alone, etc.]. She becomes, almost unconsciously, a caricature of an saleswoman, rather than a fully self-actualized and emergent personality; a person who identifies herself as being an salesperson, rather than as a person who, for now, happens to work in sales.

One of my business partners, Dr. Moss A. Jackson, would describe self-stereotyping as a limiting belief. Limiting beliefs are always dangerous because they deter us from achieving our full potential. I know that fell into this trap from time to time in my professional career in finance and accounting. Because I have a gift for working with numbers, people came to see me as a “numbers guy,” and I fell into the habit of thinking of myself in the same terms, and acting more and more in the role of the stereotypical Numbers Guy. As I withdrew into this belief-limited role, my ability to have a positive influence on the development of our business was diminished. Luckily, I had a good coach and mentor who helped me realize that I wasn’t simply the Numbers Guy. I had the potential to be a top-flight business person who happened to be blessed with a special affinity for working with numbers. Freed from my limiting belief, I was able to focus on what I needed to do to enhance my skills and improve my ability to contribute in many ways to the growth and development of our business.

One of my business partners, Dr. Moss A. Jackson, would describe self-stereotyping as a limiting belief. Limiting beliefs are always dangerous because they deter us from achieving our full potential. I know that fell into this trap from time to time in my professional career in finance and accounting. Because I have a gift for working with numbers, people came to see me as a “numbers guy,” and I fell into the habit of thinking of myself in the same terms, and acting more and more in the role of the stereotypical Numbers Guy. As I withdrew into this belief-limited role, my ability to have a positive influence on the development of our business was diminished. Luckily, I had a good coach and mentor who helped me realize that I wasn’t simply the Numbers Guy. I had the potential to be a top-flight business person who happened to be blessed with a special affinity for working with numbers. Freed from my limiting belief, I was able to focus on what I needed to do to enhance my skills and improve my ability to contribute in many ways to the growth and development of our business.

Remember that you are always more than the the job you currently do or the position you currently fill. Life will present you with plenty of challenges on your journey to be the best that you can be. Don’t detour yourself with a useless self stereotype.

To stereotype is to generalize; to generalize one needs to utilize more of the brain than any other type of thinking. Unlike numbers thinking or thought problems the entire brain lights up in a CAT scan when one is asked to generalize, to give a wise answer.

Your positive spin on stereotyping is well said and wise.

I was doing a web search looking for more information on stereotypes for a 5th grade class I teach and I found your article. Thanks for exploring the etymology of the word in a way that I can make practical to the students, as well as adding the twist to think about ways we allow ourselves to accept and live up to our own stereotyped persona. That was just the journaling assignment I needed! Great information! thanks.

Susan,

While I certainly didn’t intend this piece to be for 5th graders, I’m thrilled that oyu were able to put it to good use in your classroom. You may want to take a look at an article I wrote previously, “The Tale of the Peacock’s Tail.” Your students might have fun with it.