I read a fascinating Fast Company article the other day, describing the emergence of a new position in the C-Suite of a number of large companies–that of Chief Storytelling Officer (CSO). While the article, written by Michael Grothaus, notes that perhaps the first person to hold the CSO title was Nelson Farris at Nike in the late 1990’s, a search of the business-oriented social media site LinkedIn will find around twenty-five executives who have held that position.

I read a fascinating Fast Company article the other day, describing the emergence of a new position in the C-Suite of a number of large companies–that of Chief Storytelling Officer (CSO). While the article, written by Michael Grothaus, notes that perhaps the first person to hold the CSO title was Nelson Farris at Nike in the late 1990’s, a search of the business-oriented social media site LinkedIn will find around twenty-five executives who have held that position.

It’s not that companies have suddenly discovered and fallen in love with the idea of “the story.” Marketers have been devising and telling stories about their companies and their products to customers for as long as people have been buying and selling products and services. It’s not hard to imagine a merchant in an ancient Greek marketplace explaining to a potential customer why the sandals he was selling were the very best sandals, made of the highest quality soft, supple leather that would form itself to his foot like a second skin, yet would last forever. So why the seemingly sudden interest in corporate storytelling?

MIT Sloan School of Management Lecturer Leigh Hafrey shed some light on that subject when he was interviewed at The Power of Storytelling 2014 Conference in Amsterdam on the connection between good leaders and good storytellers. When asked how storytelling can be used as a leadership tool he replied:

MIT Sloan School of Management Lecturer Leigh Hafrey shed some light on that subject when he was interviewed at The Power of Storytelling 2014 Conference in Amsterdam on the connection between good leaders and good storytellers. When asked how storytelling can be used as a leadership tool he replied:

Storytelling supplies a narrative logic to events past, present, and future. Presentations by definition work with the principles of storytelling: plot, place, character, conflict and resolution.

Some people do it better than others, and those individuals reach leadership positions in part because of their skill as storytellers. Think Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Aung San Suu Kyi, Muhammad Yunus and Vaclav Havel. Havel also exemplifies the way in which oppositional figures can take their divergent views into positions of institutional authority, as storytelling presidents, monarchs, corporate heads, judges, labor leaders, etc.

Mr Hafrey was also asked why is it important for a good leader to be a good storyteller. His answer was very interesting:

Mr Hafrey was also asked why is it important for a good leader to be a good storyteller. His answer was very interesting:

A good leader recognizes that a “good story” sometimes is a lie. A solid sense of the ingredients of story, either instinctive or conscious, allows the good leader to recalibrate, and find his or her way to a story that reveals its own motives, and transfers the power of interpretation and discovery to the audience.

But that doesn’t really explain what makes stories so special? Why are stories so memorable–much more memorable than a simple collection of facts or unrelated statements? Why is it that, as Mark Turner noted in his book The Literary Mind,

most of our experiences, our knowledge, and our thinking are organized as stories.

A possible answer can be found in a developing branch of psychology, known as narrative psychology, which is concerned with how we human beings deal with our experience of life by constructing stories and listening to the stories of others. Narrative psychology operates from the premise that our experience of life isn’t determined by logic, argument, or rule-based formulations; rather, our experience of life is largely propelled by the “meaning” we provide, via the stories we construct to make sense of the experiences that life parades in front of us.

In effect, narrative psychology argues that our experience is not simply the result of indisputable, personal physical occurrences that impinge upon our senses, but, instead, what we “experience” is the result of the stories we construct to make sense of it all–the personal and idiosyncratic interpretations of events that we construct–based on how we “read” the story.

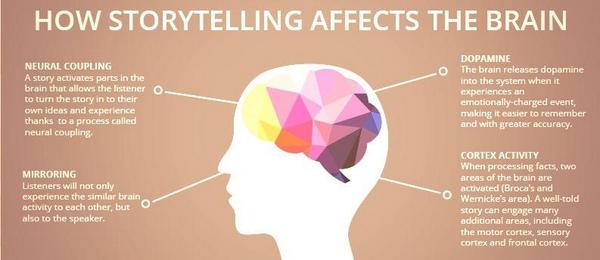

Work by neuroscientists supports the concept of narrative psychology by providing some important discoveries about stories, including how the mind processes and works through them.Through fMRI [Functional Magnetic Resonance Imagery] scans of the brain, we know that when presented with facts and figures, only two brain regions are engaged; but stories can activate up to seven brain regions.

Work by neuroscientists supports the concept of narrative psychology by providing some important discoveries about stories, including how the mind processes and works through them.Through fMRI [Functional Magnetic Resonance Imagery] scans of the brain, we know that when presented with facts and figures, only two brain regions are engaged; but stories can activate up to seven brain regions.

We now also know that our brains are wired to experience emotions by proxy. When we see another person doing something, our so-called ‘mirror neurons’ fire and trigger a response in our own brain that is similar to the response we’d have if we were doing the same thing ourselves. This appears to be the basis for human empathy, and for our emotional involvement in storytelling; we literally feel the emotions that the characters in our stories are feeling. [If you’d like to dig a little deeper into how our brains use narrative to make sense of the world, here’s a link to an enlightening video of Michael Gazzaniga, a psychology professor at UC SantaBarbara, describing a brain component he calls “The Interpreter.”

Groundbreaking work by Antonio Damasio, the renowned neuroscientist who directs the USC Brain and Creativity Institute, has challenged conventional notions that human decision-making is driven purely by rational cost-benefit analyses. His work strongly suggests that emotional memories are stored in our brains, where they play a significant role in future decision-making, and has helped us understand that a purely rational appeal to someone can be far less effective in terms of driving behavior change than one that has emotional resonance.

Groundbreaking work by Antonio Damasio, the renowned neuroscientist who directs the USC Brain and Creativity Institute, has challenged conventional notions that human decision-making is driven purely by rational cost-benefit analyses. His work strongly suggests that emotional memories are stored in our brains, where they play a significant role in future decision-making, and has helped us understand that a purely rational appeal to someone can be far less effective in terms of driving behavior change than one that has emotional resonance.

So, maybe the reason that stories are so powerful is, as Dimasio says:

So, maybe the reason that stories are so powerful is, as Dimasio says:

We are not thinking machines. We are feeling machines that think.