French novelist Marcel Proust wrote that, “The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands but in seeing with new eyes.” To me, this sounds like the exact opposite of déjà vu. We all know that déjà vu feeling. It’s the distinct feeling that, even though we are in a completely unfamiliar place, somehow, we’ve been here before. According to dictionary.com, the noun déjà vu (from the French: “already seen”, also called paramnesia) first appeared in 1903, and has two meanings:

French novelist Marcel Proust wrote that, “The real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands but in seeing with new eyes.” To me, this sounds like the exact opposite of déjà vu. We all know that déjà vu feeling. It’s the distinct feeling that, even though we are in a completely unfamiliar place, somehow, we’ve been here before. According to dictionary.com, the noun déjà vu (from the French: “already seen”, also called paramnesia) first appeared in 1903, and has two meanings:

- the illusion of having previously experienced something being encountered for the first time

- disagreeable familiarity or sameness: The new television season had a sense of déjà vu about it–the same plots and characters with new names.

The late comedian George Carlin, in one of his comedy routines, coined the phrase, vuja de to describe the feeling that “none of this has ever happened before.” Vuja de hasn’t made it’s way into the formal lexicon but the Urban dictionary provides a few attempts at a definition, all of them a variation on Carlin’s theme of coming to a familiar place and finding something new and different that you’ve never seen before. Proust might have balked at being linked with George Carlin, but I think Carlin’s phrase captures the essence of Proust’s quote, since vuja de must be akin to having a fresh set of eyes to see the same thing as everyone else, but understand it in a unique way. As an aside, Carlin’s ability to bring that sense of vuja de to his observations of everyday life were the essence of his comedic genius.

The late comedian George Carlin, in one of his comedy routines, coined the phrase, vuja de to describe the feeling that “none of this has ever happened before.” Vuja de hasn’t made it’s way into the formal lexicon but the Urban dictionary provides a few attempts at a definition, all of them a variation on Carlin’s theme of coming to a familiar place and finding something new and different that you’ve never seen before. Proust might have balked at being linked with George Carlin, but I think Carlin’s phrase captures the essence of Proust’s quote, since vuja de must be akin to having a fresh set of eyes to see the same thing as everyone else, but understand it in a unique way. As an aside, Carlin’s ability to bring that sense of vuja de to his observations of everyday life were the essence of his comedic genius.

Abraham Wald’s Airplanes

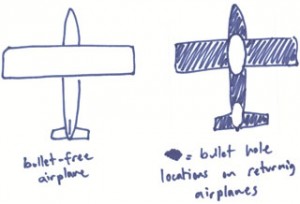

An often quoted example of this “seeing with fresh eyes” is the story about Hungarian statistician, Abraham Wald, who worked during World War II with the UK Air Ministry. British bombers were being shot down over Germany, and it made sense to reinforce the planes with armor. You can’t armor plate the entire aircraft, because the plane would be  too heavy to get off the ground. Wald was asked to perform a statistical study to answer the question, “Where should we place the armor?” Records of the planes returning from Germany showed where they had been hit, sometimes with very large holes in the aircraft extremities. So the Air Ministry wanted to put armor plate on all of the areas that showed heavy damage. But Wald pointed out that there was no data on bombers that didn’t return from Germany. He then carefully noted the few areas of the bombers where holes were NEVER found. These were the areas that Wald said needed heavy armor, because any bomber hit in those areas must not have been able to make it back to England. Obvious, but only after someone who looked at the data with fresh eyes pointed it out in a way that caused the Air Ministry to see that what had previously seemed “obvious” to them was obviously wrong. The folks at the UK Air Ministry were fooled, because they saw what looked like a pattern and made a wrong interpretation. They ignored the pattern that they couldn’t see; the pattern of bullet holes in all of the bombers that were shot down.

too heavy to get off the ground. Wald was asked to perform a statistical study to answer the question, “Where should we place the armor?” Records of the planes returning from Germany showed where they had been hit, sometimes with very large holes in the aircraft extremities. So the Air Ministry wanted to put armor plate on all of the areas that showed heavy damage. But Wald pointed out that there was no data on bombers that didn’t return from Germany. He then carefully noted the few areas of the bombers where holes were NEVER found. These were the areas that Wald said needed heavy armor, because any bomber hit in those areas must not have been able to make it back to England. Obvious, but only after someone who looked at the data with fresh eyes pointed it out in a way that caused the Air Ministry to see that what had previously seemed “obvious” to them was obviously wrong. The folks at the UK Air Ministry were fooled, because they saw what looked like a pattern and made a wrong interpretation. They ignored the pattern that they couldn’t see; the pattern of bullet holes in all of the bombers that were shot down.

Our Pattern-Matching Minds

The human mind is an amazing pattern matching machine. Our ability to recognize and act upon patterns from a small sample of data characteristics allows us to transit the exigencies of our daily lives without having to consciously think about everything that we do. We can develop heuristics–rules of thumb–that help us make decisions almost without conscious thought. Remember what it was like as a child learning to brush your teeth, or a teenager learning to drive. Every action was strained and difficult, requiring careful thought. These are actions we perform today almost automatically. We’ve learned the physical patterns of handling the toothbrush and steering the vehicle.

We do the same kind of thing in our thinking processes. We observe patterns, and make  fast decisions based on what those patterns tell us. Unfortunately, as with Wald’s Airplanes, our pattern-matching isn’t always correct. In fact, it’s often disastrously off the mark. Our minds are subject to a broad array of conceptual and perceptual errors that assail our ability to truly think straight. (If you are really interested in exploring how well, and how poorly, our thinking processes work, I highly recommend you take a look at Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman’s latest book, Thinking Fast and Slow. If that sounds familiar, it may be because I mentioned his book in a previous post.)

fast decisions based on what those patterns tell us. Unfortunately, as with Wald’s Airplanes, our pattern-matching isn’t always correct. In fact, it’s often disastrously off the mark. Our minds are subject to a broad array of conceptual and perceptual errors that assail our ability to truly think straight. (If you are really interested in exploring how well, and how poorly, our thinking processes work, I highly recommend you take a look at Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman’s latest book, Thinking Fast and Slow. If that sounds familiar, it may be because I mentioned his book in a previous post.)

But what’s maybe even more disconcerting than what we get wrong in our thinking, is what we fail to see that is right there in front of us–the things that are so obvious once  they’ve been pointed out. Studies show that airport security staff miss a huge proportion of the weapons that authorities send through x-rays as a test. Should we be horrified: how could something as unambiguous as a gun not stand out? Psychologists like Kahneman know the answer: because guns are so rare the screeners don’t see them, the bags with the weapons simply merge with the “pattern.” of bags without guns. So, beguiled by pattern, the screeners can’t see with fresh eyes, and they fail to notice the gun.

they’ve been pointed out. Studies show that airport security staff miss a huge proportion of the weapons that authorities send through x-rays as a test. Should we be horrified: how could something as unambiguous as a gun not stand out? Psychologists like Kahneman know the answer: because guns are so rare the screeners don’t see them, the bags with the weapons simply merge with the “pattern.” of bags without guns. So, beguiled by pattern, the screeners can’t see with fresh eyes, and they fail to notice the gun.

But sometimes, people find ways to look with fresh eyes. Companies were making cell phones and PDAs for years, but Apple, with the iPhone and apps, looked beyond the communications functions of the device and saw it as the smartphone, personalized and loaded with our apps and data until it has become almost indispensable, more like a part of our body than an appliance. The Amazon Kindle and its copycat eReaders are a similar phenomenon, as are wheels on suitcases, though we put a man on the moon before we figured that one out. Obvious once you’ve seen it.

A vuja de Switch

Perhaps what we need is a “vuja de switch” that we could turn on in our brains when we get too bound up in conventional thinking. That seems to a major theme of the book, Practically Radical, by Bill Taylor, co-founder of Fast Company magazine. Perhaps, as Oliver Burkeman wrote in his review of Taylor’s, book published in The Guardian, “‘Think outside the box’ has been put back in its box. Vuja dé is in.”

Unfortunately, as Burkeman points out, recommendations for vuja de thinking are essentially replacements of old thinking routines with new and different routines. The key word here is routines. Again quoting Burkeman, “The point of vuja dé is to think outside preworn grooves, but a book telling you how to think is to some extent by definition a preworn groove.”

There are some possibilities, though. Thinking about a problem in different physical  circumstances seems to help, which perhaps explains why BFOs (Blinding Flashes of the Obvious) often strike when we leave our desks and step outside for a walk in the fresh air. Selecting the reference frame of a different person–an engineer, an actor, a cook–and considering what they would do can also be a very powerful way to bring a fresh sense to our own eyes. But if the key is to randomly shift perspective to trigger new outlooks, we are in trouble without that vuja de switch. Without an outside intervention to jolt us, our pattern-seeking brains will follow the familiar and well-worn pathways, and ignore what is right in front of us, if only we would look for it.

circumstances seems to help, which perhaps explains why BFOs (Blinding Flashes of the Obvious) often strike when we leave our desks and step outside for a walk in the fresh air. Selecting the reference frame of a different person–an engineer, an actor, a cook–and considering what they would do can also be a very powerful way to bring a fresh sense to our own eyes. But if the key is to randomly shift perspective to trigger new outlooks, we are in trouble without that vuja de switch. Without an outside intervention to jolt us, our pattern-seeking brains will follow the familiar and well-worn pathways, and ignore what is right in front of us, if only we would look for it.

The best advice on this subject may be found in the book, Zen Mind: Beginner’s Mind, where Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki wrote: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities. In the expert’s mind there are few.” If we could approach the world with the wonder of a child, unburdened by the weight of our worldly experience and the numbing patterns it triggers, what might me be able to discover?

very good , Dave…one of your best.

I am very suspicious of a child-like mind. While they may be fresh they too often insist on heuristic solutions to complex problems….they outnumber us and dominate the political arena…..it’s the tragic flaw of the human race…we’re doomed

I’m not excited about childlike minds myself.

What does intrigue me is the sense of wonder with which a young child approaches the world. Everything is new, and is experienced for the first time. Nothing is boring or mundane. Nothing is subject to being dismissed because: “Been there. Done that.”

Even those of us [you and me hopefully] who have developed the capacity for advanced rational thought, are usually trapped by our own unavoidable pattern-matching, especially when we have stored away a useful heuristic, a rule of thumb that usually works to help make a snap decision. We could all use a ‘vuja de switch” to help us avoid applying old solutions to complex new problems that we mistakenly identify and categorize as “just like the problem I solved back in the day.”

Hi Dave, I stumbled onto you in some systems research. Really enjoyed this post on patterns; totally agree that “child-like minds” aid our ability to maintain objectivity from our default settings. Of course I’m a zen practitioner so you’re preaching to the choir here 🙂

I have a question about your Forbes article on change: Your theory that “change is the default setting” and we simply need the right nudge to remove the blockage is interesting… yet I am thinking about entrenched social problems (obesity, poverty, gun violence, etc) that involve a multitude of players, most of which are invested in maintaining the status quo. Your work is typically within an organization, yes? But what happens when a corporation is the problem… when they meet their short-term shareholder obligations by doing harm? Or when policymakers intent on re-election continue to make decisions that are in the best interest of lobbyists and not of society? These problems are not easy fixes… no one has yet found the “nudge” to suddenly transform us into a safe and just society. I’d be quite interested to hear if your group has tackled any of these types of problems from a systems perspective, and what’s required to affect large-scale change.

Happy new year!

Jennifer, Happy New Year and Welcome to Ubiquitous Wisdom.I hope you decide to subscribe to the blog.

Your question is intriguing, but not a new one. I wish I had a short, happy answer, but I don’t. In my work with Dr James Wilk and Alan Engelstad at international think-tank Interchange Associates, we often pondered how we might apply our method to issues such as peace in the Middle East. Theoretically,the appropriate nudge could make all of the difference.The challenge when working with such extraordinarily complex systems is filtering out the many seemingly important but essentially irrelevant factors, so that you can focus on the systemic constraints that bind behaviors into the current, dysfunctional mess. If the constraints can be isolated, then it is possible to experiment with changes to the constraints, looking for the smallest necessary change to constraints (“the nudge”) that will generate, with a high degree of certainty, the desired catalytic change.

I suggest you go to website http://www.InterchangeAssociates.com and download the papers “Realizing Possibilities” and “Wilk on the Nudge.”

If you’d like to carry on the conversation, please feel free to contact me via email at dfranzetta@gmail.com.

Hi Dave…(September 5, 2013)

I have been interested in Creativity and Intuition for many years. I thought perhaps you would be interested in my personal experiences with “Synchronicity”… and the term “Fresh Eyes”.

(1) I was searching for “Clues” about “Creativity” and I happened to notice an old Film by an Avant garde Russian Artist in the early 1920’s. It had many random scenes strung together of Parks and soldiers cities and children in Black and White. One of the subtitles said… “Fresh Eyes”.

(2) The next day I overheard two bankers talking on the street … and one of the bankers mentioned they needed “Fresh Eyes” to solve a financial problem about real estate.

(3) The following night I was watching an old Star Trek Movie … and Spock said to Kirk… we need “Fresh Eyes” to solve this problem.

Sincerely.

UFO JIM

Isn’t it fascinating how, once we “notice” something, like you noticed the phrase “Fresh Eyes,” the Universe seems to present it to us over and over in short order. I wonder if it’s nothing more than a heightened sense of focus that allows our senses to capture what would otherwise fly past without grabbing our attention.

Great blog! Thanks for sharing these thoughts, Dave. I’m coming to more deeply understand the importance of curiosity in our lives. Our habits of thought easily block our curiosity – “Nothing new here, just move on” they habits say, when there can be something very new. We do need fresh eyes. And I think you’re right to suggest that a meditative approach can perhaps, done right, refresh our sight and thoughts.

Thanks for the great musings.